The contemporary critique is tediously familiar. Hierarchy “oppresses,” “infantilises,” “kills innovation,” “reproduces inequality,” “violates autonomy,” and “lacks legitimacy.” Flatness is sold as liberation; networks as natural law; “agility” as elixir. The anti-hierarchy catechism blends liberal free-choice-fetish, critical theory’s power paranoia, and managerialist efficiency worship. Question hierarchy and you are progressive; defend it and you are a closet authoritarian.

Yet the critique rests on philosophical quicksand. Liberal autonomy demands consent yet cannot ground the substantive good that renders consent morally binding—dignity collapses into “capabilities”. Critical theory exposes domination but cannot distinguish emancipation from egotism without an external criterion it refuses to justify. Pragmatic instrumentalism judges by outcomes but cannot say which values rule or why. Each borrows the language of dignity, justice, or flourishing while rejecting the metaphysical ground that makes them coherent.

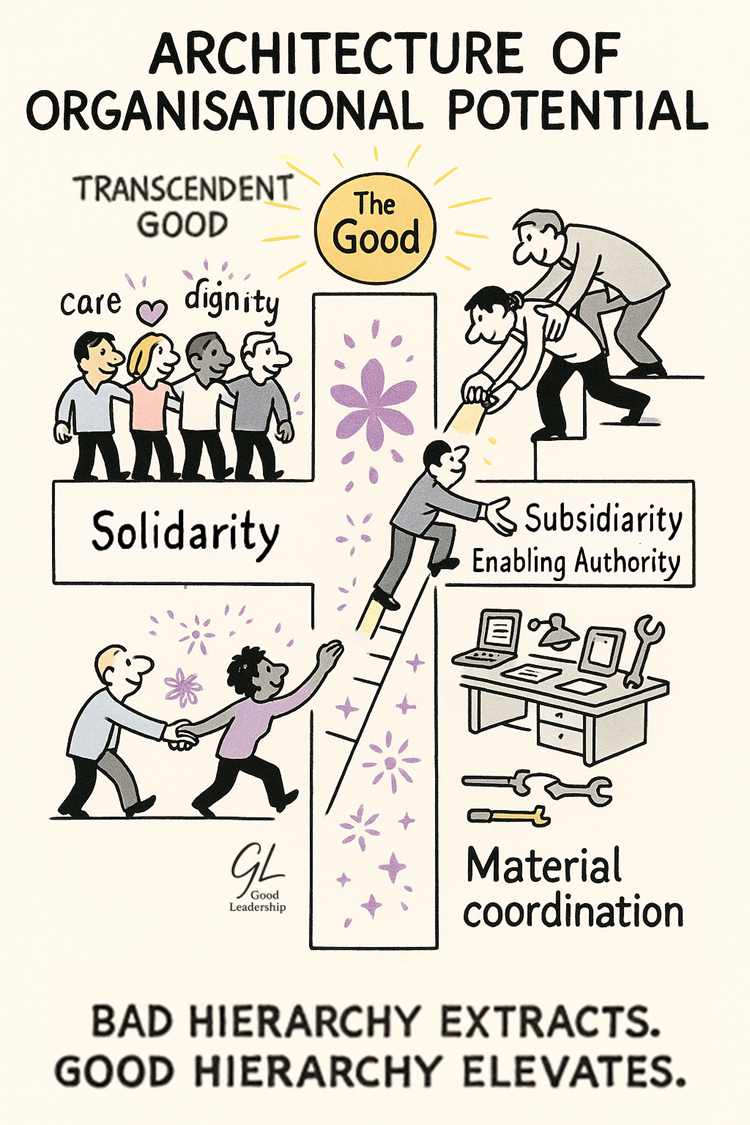

This requires a deeper anthropology. Persons do not realise their essence through self-legislated autonomy or perpetual contestation; they flourish through participation in the Good—a telos not invented by collective will but discovered and instantiated through right relation. The good society is ordered, not aggregated; constellational, not merely consensual. Higher orders exist not to overrule but to enable participation in ends transcending any individual or unit.

The mistake is conceptual: Treating hierarchy only as power flowing downward through extraction and control. But authentic hierarchy is authority flowing upward—not domination, but guardianship. Not surveillance, but cultivation. Not extraction, but investment in excellence.

Hierarchy becomes legitimate not through consent or efficiency but through analogy: does authority order individual potentials in ways enabling the flourishing of all? Managers are not mini-sovereigns nor neutral servants or personal coaches; they are architects of social potentiality, cultivating organisational character through wisdom.

Subsidiarity is an ontological—not democratic—principle: each level possesses its own proper perfection. Higher levels intervene to enable what lower levels cannot realise, not to absorb what they already can. Yes, bad hierarchy is domination; but good hierarchy is midwifery—the structured mediation through which virtue becomes collective excellence.

Flatten the hierarchy and you merely hide the ethos: informal elites emerge, coordination collapses, power becomes opaque. But redeem hierarchy—ground authority in the Good, orient it toward the flourishing of persons-in-relation—and it becomes the only structure capable of uniting personal virtue and common good without dissolving into tribalism or technocracy.

The problem is not that organisations have hierarchy. The problem is that they have the wrong kind.

#Leadership #Hierarchy #OrganisationalDesign #Philosophy #CommonGood

This post is part of a trilogy: