A few years ago, I warned that the Inner Development Goals risked becoming a well-intentioned distraction—an elegant taxonomy of superficial self-care recast as system transformation. To date, that warning has gone unheeded. Despite global uptake, the IDGs have not matured into a coherent theory of change. Instead, it has ossified into a depoliticised wellness programme for elites—a secular catechism of the managerial class, mistaking introspection for emancipation and psychological traits for moral action.

The problem is not aspiration. The problem is ontology.

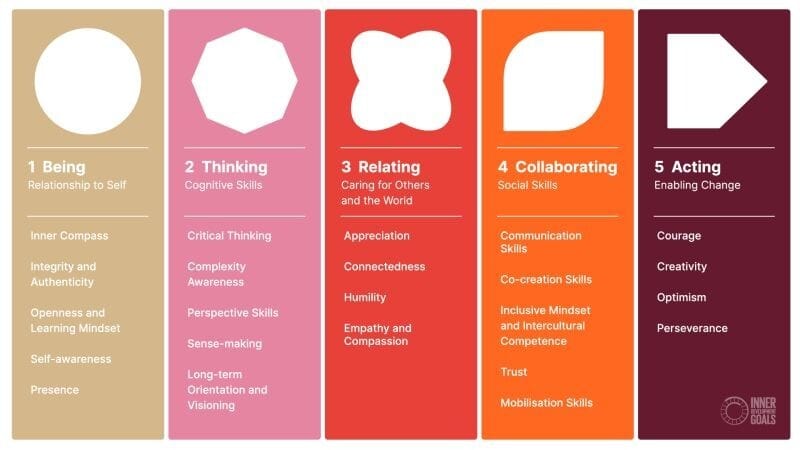

IDG treats the human being as a container of latent “capacities” to be unlocked—thinking, being, relating, acting—without ever asking what a human is, what development is for, or what the good requires. The result is a disembedded model of inner growth, shorn of existential conflict, social contradiction, and metaphysical responsibility. It offers transformation without tragedy, virtue without vocation.

What remains is a language of subjective wellness: self-awareness, openness, presence. But these are not virtues—they are neutralised affective states. The IDG architecture bypasses the moral drama of life: the struggle for justice, the weight of responsibility, the need for institutional design that shapes character. The inner is treated as a tool for self-optimisation. But in truth, the inner is political—always already structured by history, ideology, and power.

This conceptual failure has practical consequences. IDG initiatives are increasingly co-opted into HR pipelines, DEI workshops, ESG dashboards. They become tools of progressive neoliberalism: performative empathy within unchanged systems. Lacking a dialectical understanding of self and society, IDG offers no critique of the institutions it seeks to humanise. It speaks the language of becoming, but delivers only adaptation. Reflection without reconfiguration. Resilience without resistance.

Contrast this with deeper traditions. The Buddhist Eightfold Path is not a menu—it is a path of renunciation, discipline, and interbeing. Christian theosis demands kenosis, community, liturgy. Theory U requires ego death, systemic sensing, and prototyping the new. None of these can be reduced to “skills.” They are pedagogies of moral formation through shared purpose, relational conflict, and institutional struggle.

IDG has no such telos. It aims to humanise the status quo, not transform it. It avoids the real work: how to become good in an unjust world. That curriculum cannot be found in soft skills workshops or mood boards of "humility". It requires rebuilding the conditions under which moral agency becomes possible: governance for wisdom, economies for justice, education for virtue.

Unless IDG confronts its metaphysical evasions and political omissions, it will perpetuate the systems it refuses to examine. And the deeper work of moral development—the work of becoming human—will be left unfinished.

#Leadership #MoralDevelopment #SystemsChange #Philosophy #CriticalThinking

See also:

For the extensive conversation see: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ottivogt_idgs-leadership-activity-7344297827918901248-dajH?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAABm1WMBiwxFaUc1X66gje88odJOEyNAskc

Selected Q&A

Q- This is a necessary critique. I agree that the IDGs risk becoming a depoliticised wellness programme if they remain disconnected from systemic and structural transformation. Inner work without addressing root causes can reinforce the status quo and lead us into a sunk cost fallacy – investing in self-development without creating real change. At the same time, I believe the IDGs still hold an important place. They are not the solution in themselves, but they can enable solutions if integrated wisely. Inner development is a leverage point: it creates the courage, clarity, and relational capacity needed to take meaningful action in the world. But action must be built on collective visions and structures for systemic change – otherwise it remains personal adaptation rather than transformation. This is what emergence is all about – shifting from the epistemological to the ontological. Inner growth must be linked to outer change, shaping institutions, economies, and cultures towards justice and regeneration. For the IDGs to avoid becoming merely a managerial self-help tool, they could integrate practices that connect personal development with collective action, institutional critique, and political purpose. In doing so, they would not just humanise the status quo, but help us reimagine and rebuild it.

A- Beautifully put - but I think it still underestimates the ontological and epistemological flaws baked into the IDG framework itself. The issue is not merely one of integration—i.e., whether inner development is accompanied by systemic change—but of the very foundations and methodology through which the framework was constructed. The clustering process, rooted in eclectic expert interviews and crowd-sourced consensus, lacks a coherent theory of the self, development, or moral purpose. It produces an aggregated psychologism that presumes universality while evading normative grounding. As such, the IDGs do not simply risk becoming self-help—they are designed around a managerial epistemology that treats inner capacities as levers for external efficacy, not as expressions of a dialectical, socially situated moral subject. “Linking” inner and outer thus won’t suffice. What’s required is a reconstitution of the framework’s philosophical scaffolding—from virtue ethics, critical realism, and traditions of moral formation—that recognises development not as emergent adaptation but as moral becoming in response to contradiction. Without this, the IDGs may inspire, but they cannot transform.

Q- Is it necessarily a failure of the framework that it offers useful tools for developing important skills but does not seek to become a religion or offer an all-encompassing philosophy? Without a doubt the things you point out as absent in the IDGs are critical for precisely the reasons you say—I agree that without them we will not see real, necessary change in the right direction—but perhaps their omission is intentional because those needs are better met elsewhere and being prescriptive about them could be less inclusive, even alienating for some. IDGs can be—and frequently are—applied poorly and superficially in ways that serve the status quo, but religions and philosophies are often misunderstood and abused too. It doesn’t change the fact that the IDG’s skills and tools are valuable and are poorly taught or absent in the mainstream. Done right, using the IDG framework doesn’t have to result in navel gazing and fancy but shallow efforts at personal wellness.They can and should develop interpersonal skills and encourage pro-social action without hubris. For those who don’t already have compatible sources of moral and ontological guidance, they are likely to encourage enquiry into the wisdom you fault them for lacking.

A- A fair provocation. But the crux lies not in demanding that the IDGs become a religion or all-encompassing philosophy, but in recognising that any developmental framework implicitly rests on ontological and ethical premises, whether acknowledged or not. To eschew metaphysical commitment in the name of inclusivity is not neutrality, but a tacit embrace of liberal individualism: a procedural ethics of self-cultivation divorced from a shared telos. That is itself a worldview—with consequences.

The risk is not merely superficial application (which afflicts all systems, as you rightly note), but structural under-specification: the IDG’s abstract skill clusters do not guide the formation of practical judgment (phronesis) nor orient individuals toward a substantive vision of the good. Instead, they prioritise psychological fluency over moral discernment, producing what Bhaskar might call a “flat” ontology—human development without a purposive arc.

Moreover, while the IDGs might stimulate further inquiry in some, that potential cannot substitute for responsibility in design. If a framework is used to shape leadership, education, or governance, then evading its own normative assumptions becomes ethically precarious.

Q- I don’t disagree. They could be seen as not taking a sufficiently direct political or philosophical stand, leaving these thing implicit for better or worse. I’d say that the skills they encompass are necessary but not sufficient. As for telos: were they not intended to support our collective achievement of the UN’s SDGs? Those goals may well be critiqued in their own right (especially #8), but they give the IDGs their purpose. Not saying that the SDGs are of sufficiently high purpose, but that’s the level of ambition and it’s not worthless.

A- Great point. You’re right that the IDGs gesture toward normative purpose by linking to the SDGs—but this cannot constitute a telos in the Aristotelian or Thomistic sense. The SDGs are technocratic targets derived from global consensus, not expressions of formal or final cause; they presuppose but do not substantiate an anthropology of the good. Without ontological commitments to human flourishing, justice, or the good life, instrumental alignment with the SDGs becomes ethically hollow. Not to even talk about the inconsistencies of the SDGs ;-). Worse, if skills development serves externally defined goals without reflexive grounding in virtue or phronesis, we risk perpetuating the very pathologies we aim to transcend. True telos is not a strategic aim but a moral horizon that orders development, and personal development does not simply imply delivering some unexamined externally imposed technocratic targets. PS: Not to even mention the ethical challenges of so-called "science-based" targets

Q- The duality in this exchange is not a weakness to resolve but precisely the tension we need to hold. On one side, we see a critique that the Inner Development Goals (IDGs) lack ontological and moral grounding. On the other, a defence that they remain useful precisely because they do not prescribe a single philosophy of life. This reveals a deeper truth: governance frameworks and tools such as the IDGs should not aim to harmonise thought but to harmonise action. It is neither possible nor desirable for a framework like the IDGs to dictate what people should believe about the ultimate meaning of life, justice, or morality. Human societies thrive on diversity of thought, culture, and metaphysics. What is needed is a shared capacity for action—to respond collectively to crises and opportunities in ways that are grounded, ethical, and effective. The IDGs are, at their core, tools. They provide psychological, emotional, and interpersonal skills that enable people to engage, reflect, and act with greater awareness and relational sensitivity. The danger is not in their incompleteness—they were never designed to be a moral philosophy or religion. The danger lies in the illusion that they are sufficient on their own. Introspection and inner growth are essential, but they do not automatically translate into systemic change. History is replete with examples of highly “developed” individuals who upheld or enabled unjust systems. The true potential of the IDGs is unlocked when we reorient their use from individual flourishing alone toward collective restraint, solidarity, and transformative action. For example, many climate activists use IDG-based inner practices to avoid burnout or post-traumatic stress after frontline actions. Here, inner development is not an end in itself but a means of sustaining moral courage and collective agency. Therefore, we must hold both truths simultaneously: 1. That the IDGs lack a moral telos and should not be mistaken for one. 2. That their tools are invaluable when embedded within broader frameworks of ethics, justice, and systemic transformation. In this duality lies their greatest promise. They can be repurposed to enable not just personal wellness or professional efficacy, but also the inner resilience, humility, and courage required for collective action toward systemic change. This is their role: not to harmonise thought, but to harmonise and sustain action in pursuit of a more just and flourishing world.

A- Well said, but I think there are some basic flaws in the argument. 1. The claim that this is “the tension we need to hold” presents a false compromise between two incommensurable positions: the need for ontological and moral grounding versus the value of non-prescriptive pluralism. This is not a dialectical tension to be held, but a category error. You cannot deploy a developmental tool intended to enable ethical action without presupposing a normative ontology of the self, society, and the good. As such, the defence that IDGs “should not dictate beliefs” evades the fact that any framework for action already carries implicit metaphysical and moral assumptions, whether declared or not. 2. The argument posits that the IDGs are merely "tools" that "do not prescribe a philosophy of life" yet can support transformation. This reveals a tacit instrumentalism that disavows its own epistemic commitments. A tool is only meaningful within a teleological frame: What is it for? Who defines its success? Saying a tool supports “collective agency” presumes an understanding of agency, collectivity, and moral action—which are not value-neutral categories (cf the critique to Rawls counterfactual "right before good" approach in his Theory of Justice). The claim that “history is full of highly developed individuals who upheld unjust systems” undercuts the very developmental assumptions of the IDGs: if inner development is disconnected from moral formation, the tool is epistemically vacuous. 3. The notion that the IDGs can support transformation through “shared capacities for action” neglects the moral anthropology that underpins all education and development. As Aristotle, MacIntyre, and Nussbaum have shown, virtue is not a psychological skill, but the cultivated alignment of character with the good. The attempt to define ethics as a matter of “relational sensitivity” and “inner resilience” reduces morality to affective functionality, bypassing normative judgment and public reasoning. And finally, 4. The claim that IDGs are not a telos but can support action toward a “more just and flourishing world” reintroduces teleology by the back door, without providing the criteria for justice or flourishing. It assumes a shared normative endpoint while denying the necessity to articulate or ground it. This is a performative contradiction: it relies on a moral aim while disavowing the responsibility to justify it.

In sum, this popular kind of argument fails to justify how tools could be value-neutral, and how "value-neutral" tools could lead to morally grounded action. It relies on an unacknowledged liberal proceduralism, presuming that ethical convergence will emerge magically from the interplay of plural perspectives and enhanced capacities. But as the history of moral philosophy and political education shows, without an explicit account of the good and a pedagogy of judgment, we risk precisely what you warn against: the co-optation of tools for system maintenance, not transformation. The solution is not to "hold the tension," but to clarify and dialectically confront the ontological commitments that any serious moral or educational framework must make.

Q- You are talking as if Kantian and western morality systems were shining absolutes that anyone can apprehend, maybe through Nous, as in Aristotle. It is easy to play the ontological card and then leave the table, without ever questioning who will pick up the card and what will be read into it. If we are at this collapsing stage of "modernity" isn't your understanding of morality as unrelational and unaffective in itself the problem?

A- A fair provocation—and one worth sharpening. But I would argue the opposite: that the collapse of modernity stems not from ontological overreach but from moral evacuation as Charles Taylor argues—specifically, the disembedding of ethics from relational, institutional, and metaphysical grounding. We create "buffered" and "unencumbered" selfs, without questioning the ontology of self itself. My critique is certainly not a defense of Kantian deontology - I am not quite sure where that idea comes from - but of moral realism broadly construed: the claim that moral truths, though mediated by relation and affect, are not reducible to them.

Far from treating morality as “unrelational,” I argue it must be more relational—not simply as intersubjective sentiment (a la Hume, TMS or care ethics alone), but as situated within shared institutions of meaning, capable of sustaining orientation toward the good across plural and conflictual lifeworlds. The ontological card is not a dodge—it’s a call to recover the moral depth modernity has flattened: not to assert absolutes, but to reawaken our responsibility for truth, value, and the common good beyond expressive individualism. To your second suggestion: No, "the lack of processual flow" between an arbitrary clustering of skill groups is certainly not the problem. ;-) That diagnosis misplaces the locus of critique. "Emergent" (whatever that really means as the social ontology is undefined here), situated flows—however nuanced—do not substitute for ontological grounding. Without a substantive account of the good, all “processuality” risks collapsing into adaptive functionalism: "capacities" might "emerge", but to what end? A framework that brackets normativity in favor of open-ended development cannot adjudicate between manipulation and maturation, between resilience and complicity. The absence of ontology is not only a philosophical oversight—it is also a political one. It prevents the IDGs from distinguishing transformation from optimisation within unjust systems. Ethics without telos is merely (unreflected) technique.

Q- This is a very rich thread. Thank you. I was peripherally involved right at the start of the IDG’s and at the time shared some concerns with the process of surfacing the various skills and themes. I have many friends involved in the movement at various levels, and have been observing with interest from the side. After reading all the interactions here I am left with this question: assuming the critiques are valid, and the framework does lack coherence and Telos. What can we collectively offer as a way forward? What the IDG community have managed to do is mobilise a very diverse and engaged network at scale (800 community nodes in over a 100 countries last I heard). Perhaps it would serve all of us better to think about finding ways to mobilise that energy towards more coherent/moral change and not wish for it to fizzle out or fail?

A- Your comment seems to suggest that large-scale mobilisation, even if built on an incoherent foundation, can still be redirected toward morally valuable ends. But I see the issue differently. In my view, the framework is structurally flawed and cannot be easily ‘retrofitted’ with depth or coherence. Energy is not ethics. Its lack of telos is not a bug—it is a constitutive feature.

For me, the superficiality of the IDGs is a symptom of a broader disavowal at the heart of late-modern institutional life. The IDGs sustain a fantasy of inner development as a compensatory response to systemic dysfunction. They avoid necessary dialectical contradiction through universalised signifiers—Being, Relating, Acting—which remain radically unanchored in any normative political economy or theory of justice. They construct an imaginary community not grounded in shared commitment to truth or good, but in shared affective resonance: a “hallelujah” of collective jouissance without rupture, sacrifice, or negation. In this sense, the IDGs are not innocent tools awaiting redeployment, but a mirror of the managerial unconsciousness of our age.

Q- I think they were introduced them to fix the leader thinking a good leader will automatically do the "right thing". However the right thing is not defined or agreed upon so I see the challenge. The IDGs are not goals in themselves. You cannot build a movement around a "how" it has to be around a "what" and a"why". Also the other gap is the definition of the shadow the "why not". Why are we not doing what we agreed to do? Maybe we are answering the wrong question. I see the value though. If the why and what is clear they can get us there. IDGs are tools not ends.

A- Yes and no. While it is true that IDGs are positioned as “tools not ends,” this instrumental framing itself is problematic. Tools are never neutral—they embed ontologies, epistemologies, and normative assumptions. And "development" is not simply about outcomes. The IDG framework, by refusing to define “the right thing” or articulate a substantive “why,” defaults to a procedural ethics rooted in individual self-management rather than moral reasoning or political responsibility. One cannot bridge the “why not” gap through capacity-building alone if the structural causes of inertia and lack of agency (power, ideology, institutional design) remain unexamined. To say we may be “answering the wrong question” is apt—but the deeper critique is that the IDGs avoid the question of justice entirely. Without an account of virtue, conflict, or the common good, they cannot mediate between plural moral claims or guide action in conditions of crisis. Ultimately, yes, you cannot build a movement around a “how.” But even as tools, the IDGs are normatively thin, ontologically ambiguous, and politically inert. They risk becoming therapeutic governance instruments for elites rather than catalysts of moral and institutional transformation.

Q- Thank you, for inviting deep reflection. Your provocation has stirred something in me: not resistance to critique, but a concern about how we frame dissent in a time when hope and collaboration are fragile yet essential. While I agree the IDGs must remain open to scrutiny, I find myself asking: how might we challenge and evolve them without eroding the trust and commitment of those working earnestly from within? Your question about the telos (our shared purpose or aim) is important and one I’ll explore further in a post I feel compelled to share soon. For now, I hope we can hold space for both rigour and regeneration. Critique, yes, but let it be critique in service of coherence, not collapse

A- Thank you for this generous and thoughtful reflection. I fully agree: the aim is not to dismantle, but to deepen—to move from enthusiasm to integrity. Rigour without regeneration, like justice with care, becomes sterile; but regeneration without rigour risks incoherence. Far too many "popular" yet unqualified leadership/development frameworks crowd out the necessary moral reflections and political actions of our age. My hope is that critique, rightly held, can be an act of care—one that honours the sincerity of the movement by helping it grow roots strong enough to bear real fruit. I look forward to your post.