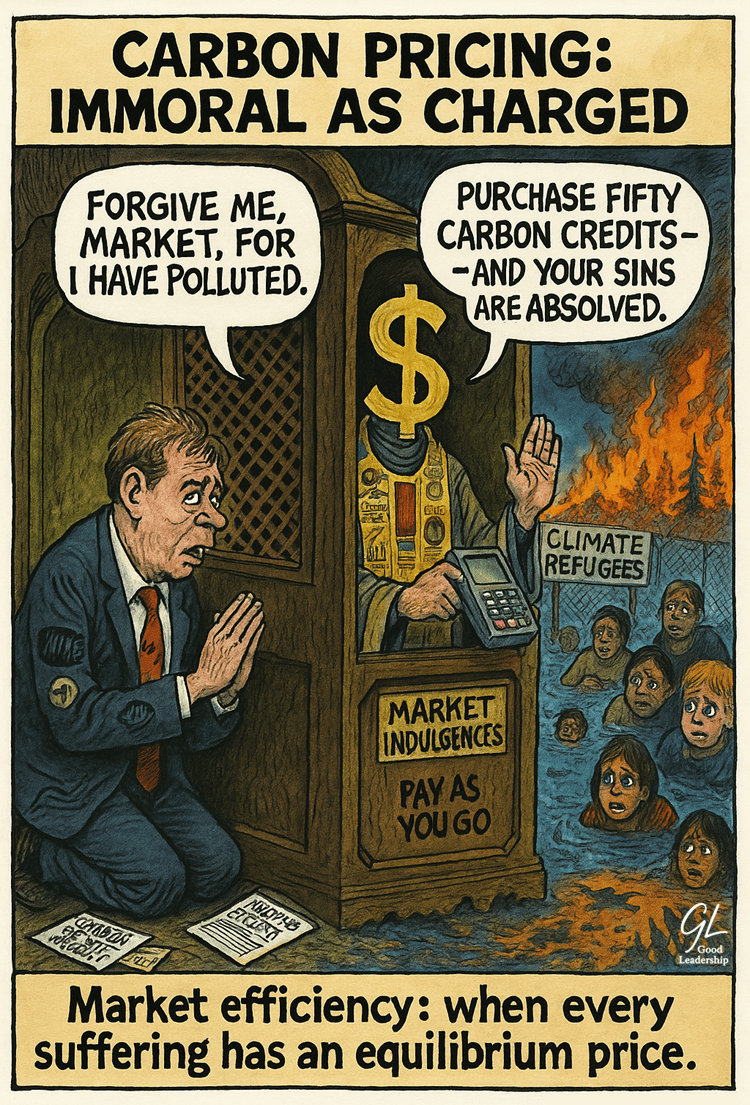

Imagine a courtroom where some of humanity's greatest moral traditions sit in judgment: utilitarianism, Kantian ethics, virtue ethics, care ethics, contractarianism, dialogue ethics, Christian teaching, and Buddhism. Before them stands carbon pricing—the flagship climate policy that puts a price tag on planetary destruction while promising market-based salvation.

The verdict is in, and it is unanimous. Carbon pricing, as implemented in every major scheme worldwide, stands morally condemned.

This is not ideological posturing. It is the result of rigorous ethical analysis applied to the concrete realities of policy. The implications for every leader who has endorsed these mechanisms are profound.

The Evidence: Market Failure Meets Moral Failure

The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme, launched in 2005 across 10,000 installations representing 40% of EU greenhouse gas emissions, exemplifies the problem. While verified emission reductions between 2005-2020 are estimated at roughly 35% in covered power and industry sectors, rigorous econometric studies attribute a substantial share of these reductions to overlapping policies, economic downturns, and renewable energy mandates rather than to carbon pricing signals alone. Meanwhile, carbon prices under the ETS exhibited extreme volatility, ranging from below €5/tonne during the surplus allowance period (2012-2018) to above €80/tonne following market reforms in 2022. This price volatility, combined with extensive free allocation provisions, generated substantial windfall profits for incumbent energy companies while distributional impacts fell disproportionately on energy-intensive industries and households.

British Columbia's carbon tax tells a similar story. Rising from CAD $10/tonne in 2008 to CAD $65/tonne by 2023, it achieved 5-15% per capita emission reductions relative to other Canadian provinces—but studies emphasize the confounding role of economic trends, cross-border fuel purchasing, and simultaneous regulations. Despite revenue-neutrality commitments, revenue recycling through tax credits and rebates delivered less than 20% of total revenues to the lowest-income deciles, while high-income households maintained consumption patterns largely unchanged, effectively purchasing continued emission rights through higher prices.

These empirical failures matter, but they don't constitute the moral case. That case runs deeper: carbon pricing institutionalizes injustice regardless of its technical performance.

Utilitarianism: The Calculus of Suffering

Utilitarian ethics requires policies that maximise aggregate well-being or minimise suffering. Carbon pricing fails this test spectacularly. In every major scheme, privileged actors buy the right to keep polluting, while those least responsible—the global poor and climate-vulnerable populations—bear the gravest consequences. Suffering is not reduced; it is systematically shifted from those with market power to those without.

This condemnation holds across utilitarian variants. Act utilitarianism finds that harms to climate-exposed populations far outweigh any marginal benefits to emitters. Rule utilitarianism, when applied to the generalisation of carbon pricing as a policy template, shows that institutionalising compensation-for-harm rather than prevention worsens collective outcomes. Preference utilitarianism, focused on satisfying the most urgent interests, exposes the systematic neglect of the most vulnerable.

Only if all revenues were transparently delivered to those most affected—fully offsetting harm and elevating collective welfare—could utilitarian approval be conceivable. No existing policy achieves this.

Verdict: Immoral.

Deontological Ethics: Commodifying Human Dignity

Kantian ethics rests on universal principles: human dignity, fairness, and the categorical imperative to treat every person as an end in themselves, never merely as a means. Carbon pricing systematically violates each of these foundations.

By commodifying harm, current schemes permit wealthy actors to buy exemption from moral duty—literally paying for the right to inflict suffering on others. This fails the universalizability test: one cannot will as a universal law a system where the powerful purchase permission to harm the powerless.

Some invoke formal autonomy—individuals supposedly choosing freely under market conditions—but this misreads Kant. True autonomy is grounded in moral law, not market power. When the vulnerable lack real agency over their exposure to climate harm or access to compensation, any claim of consent becomes grotesque.

Neo-Kantians sometimes posit that universal carbon taxation expresses collective duty, but actual policies systematically exempt major emitters through free allocations and loopholes, while permitting harm against unwilling third parties. The claim to universality collapses.

Current carbon pricing transforms justice from a moral imperative into an economic transaction. Only policies co-designed by those most exposed, which prevent rather than monetise harm, could ever meet deontological standards.

Verdict: Immoral.

Virtue Ethics: Cultivating Indifference

Virtue ethics evaluates policies by the character traits they cultivate—justice, courage, compassion, practical wisdom. Carbon pricing fosters their very opposite: technocratic abstraction, moral avoidance, and systematic indifference to suffering. The logic of instrumental rationality displaces the demands of justice and care. Through layers of market mediation, policymakers become insulated from the consequences of harm. Rather than developing the transformational courage required for climate justice, carbon pricing enables moral cowardice disguised as pragmatism.

Defenders might appeal to phronesis—practical wisdom in the face of real-world constraints. But true practical wisdom cannot justify entrenched indifference. Genuine civic virtue demands solidarity with those most affected, not fiscal mechanisms that obscure relationships of harm.

Only policies that directly embody justice and solidarity—placing those most impacted at the centre—could meet the standards of virtue ethics. No current carbon pricing scheme reflects these virtues.

Verdict: Immoral.

Care Ethics: Severing Relationships

Care ethics prioritises relationality and attentiveness to lived vulnerability. Carbon pricing treats harm as atomistic and reducible to monetary equivalents—a fundamental ontological error. Its impersonal, transactional logic systematically fails to recognise or address the needs and agency of climate-vulnerable communities. Policy remains remote, controlled by technical elites, with negligible participation or material benefit for those who suffer the greatest harm. The pricing mechanism forecloses genuine relational politics in favour of market abstraction.

Even if revenues were channelled through participatory community investment, the dominant policy form prevents any authentic relationship between those causing and those bearing climate harm.

Only policies rooted in the lived context and agency of the affected, delivering both relational and material care, could satisfy care ethics. No existing carbon pricing scheme meets this standard.

Verdict: Immoral.

Contractarianism: No Consent of the Governed

Contractarian theory asks whether reasonable actors would consent to a proposed social contract, and whether any inequality benefits the most disadvantaged. For carbon pricing, the answer is unambiguous: no.

Even comparatively generous domestic schemes—such as British Columbia’s rebates—fail the global test. Wealthy nations impose carbon pricing mechanisms on the Global South and marginalised communities without meaningful consent or reciprocal benefit. Rawlsian principles—especially the difference principle—are systematically violated.

A global carbon dividend benefiting the world’s most vulnerable could, in principle, satisfy contractarian requirements. But no such legitimate agreement underpins current policy. What we have instead is elite imposition masquerading as consensus.

Only if the least advantaged themselves co-designed, consented to, and demonstrably benefited from carbon policies would contractarian approval be possible.

Verdict: Immoral.

Dialogic Ethics: Systematic Exclusion

Dialogic ethics requires genuine participation and co-deliberation by all those affected. Carbon pricing fails catastrophically on this front. While EU processes may engage parliaments and organise consultations, those bearing the greatest climate burdens—small island nations, Indigenous peoples, subsistence farmers, and the urban poor in the Global South—are systematically excluded from policy design and decision-making.

The most impacted populations have no meaningful voice in shaping the very policies that determine their survival. Technocratic narrowness consistently overrides dialogic validity.

Procedural democracy among the already-privileged cannot substitute for inclusive deliberation with those most affected. No current policy comes close to meeting this standard.

Verdict: Immoral.

Christian Ethics: Betraying Creation and the Poor

Christian teaching demands both stewardship of creation and a preferential option for the poor. Carbon pricing violates both imperatives by commodifying the right to harm creation and systematically sacrificing vulnerable communities for economic efficiency. The preferential option for the poor is inverted: the poor are sacrificed for the comfort of the wealthy.

This represents, at root, a form of idolatry—elevating market logic above creation and human dignity.

Only policies that embody genuine care for creation and uplift the most vulnerable could satisfy Christian ethical demands. No existing carbon pricing scheme meets this test.

Verdict: Immoral.

Buddhist Ethics: Ignoring Interdependence

Buddhist ethics is rooted in the recognition of universal interdependence and the imperative to reduce suffering for all beings. The logic of carbon pricing—market-based, transactional, and reductionist—severs the intricate web linking humanity and nature, legitimising harm while privileging profit over compassion.

Market-driven schemes such as these reinforce avidyā (fundamental ignorance): the illusion that suffering can be commodified, monetised, and displaced rather than acknowledged and addressed at its source. In perpetuating this delusion, carbon pricing entrenches the very patterns of attachment and ignorance that Buddhist practice seeks to overcome.

Only policies that genuinely honour interdependence and seek to alleviate suffering at its root can be reconciled with Buddhist ethical commitments. No existing carbon pricing policy meets this criterion.

Verdict: Immoral.

The “Lesser Evil”?

Faced with this unanimous moral condemnation, defenders of carbon pricing might retreat to a “lesser evil” argument: that carbon pricing, while morally impure, is justified by political constraints, or that as a “second-best” solution, it is preferable to inaction when ideals are unattainable.

This defence fails decisively on three counts. First, it presumes an absence of viable alternatives—a stance that reflects ideological closure, not pragmatism. There is no justification for treating market mechanisms as the outer boundary of climate policy; large-scale public investment, international technology transfer, and binding global agreements with differentiated responsibilities are all serious alternatives systematically sidelined.

Second, the argument ignores the dangers of path dependence. Adopting carbon pricing entrenches market logic, generates corporate windfalls, satisfies superficial demands for “climate action,” and creates vested interests that obstruct transformative solutions. What is framed as a “bridge” often becomes a dead end.

Third, it illegitimately shifts the burden of proof. Advocates of carbon pricing must show not merely that it outperforms inaction, but that it demonstrably surpasses all credible alternatives. No such case has ever been made.

Immoral As Charged

Every major ethical tradition arrives at the same conclusion: carbon pricing, as currently institutionalised, fails the most basic moral tests. It commodifies harm, entrenches corporate privilege, excludes the vulnerable, and erodes any solidaristic political imagination.

While it is conceivable that carbon pricing could, in theory, be designed to meet utilitarian, contractarian, or even Kantian standards—through high uniform pricing, fair redistribution, and genuine participation—no actual scheme comes close.

The implications for leadership are unambiguous. Political figures who have endorsed carbon pricing, business leaders who have championed it, and policy experts who have defended it as pragmatic are, in effect, lending their authority to an architecture of systematic injustice.

Ultimately, carbon pricing functions as an ideological mechanism that converts the climate crisis—a fundamentally social and political antagonism—into a technical problem of price signals, thereby neutralising conflict over responsibility, power, and redistribution. It underwrites a loudly proclaimed “humanitarian” or “sustainable” capitalism that preserves the existing order while symbolically paying for its sins: the system can remain intact; it merely needs the right price. At its core lies the unspoken fantasy that the climate crisis can be resolved by extending the reach of the market rather than by confronting its limits. As Žižek observes, “when a problem is presented purely as a technical issue, the political choice has already been made.”

But when the world’s major moral traditions speak with a unanimous voice, ethical responsibility demands more than rationalisation or delay. It requires listening, acknowledging the depth of moral failure, and insisting on genuine transformation. Our planetary crisis calls for policies anchored in justice, compassion, and ecological integrity. When our actions are driving planetary destruction, the only moral response is to bring them to an end.

The verdict is in. The only remaining question is whether our leaders possess the courage to accept it.

#ClimateJustice #BusinessEthics #PoliticalEconomy #ESG #MoralPhilosophy