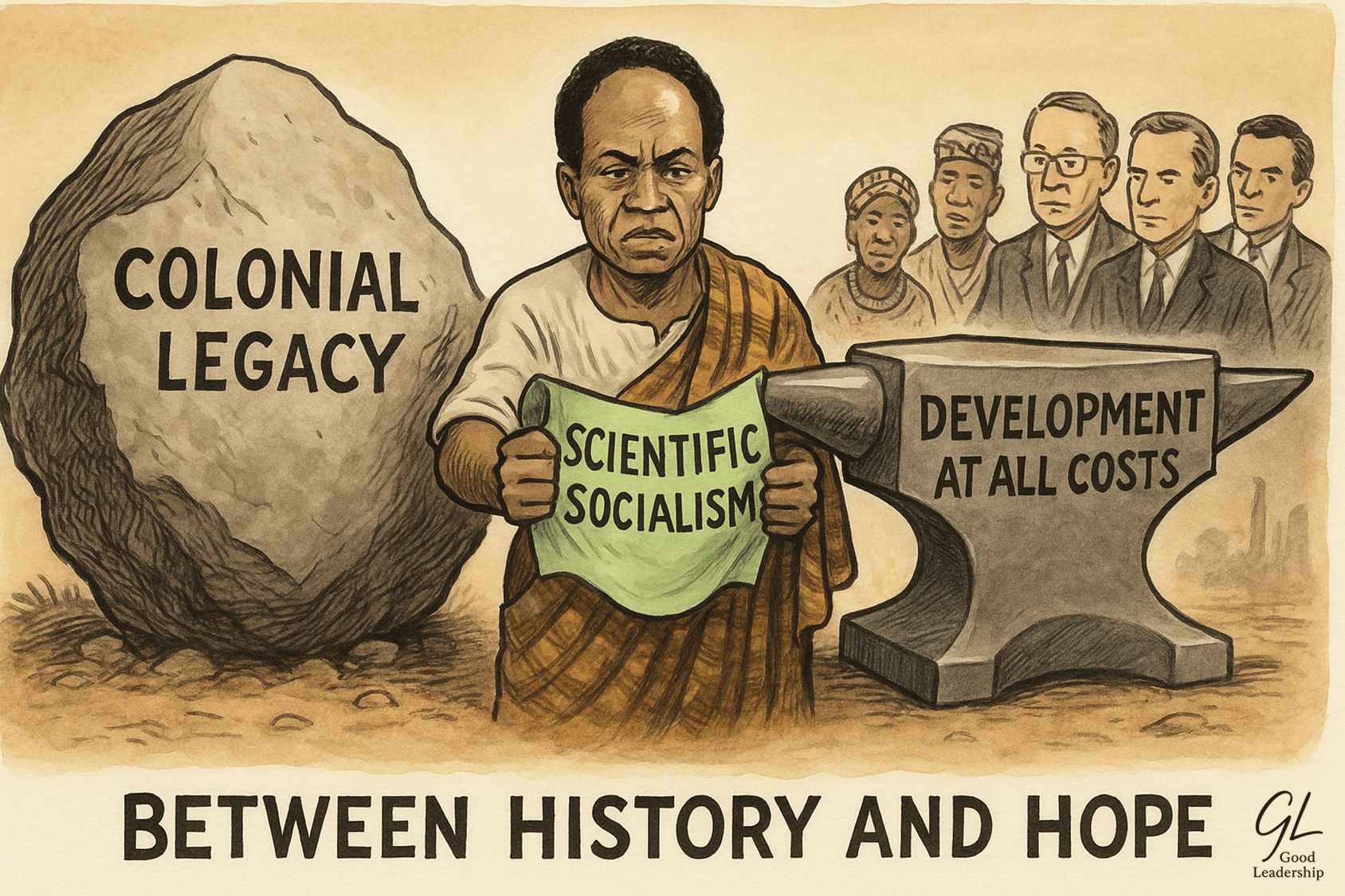

Francis Kwame Nkrumah, philosopher-statesman and radical modernizer, embodied the aspirations and contradictions of a continent in transition. Trained in the analytical rigor of Anglo-American philosophy and galvanized by the anti-colonial ferment of the 1940s, Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in December 1947 with an unprecedented ambition: to transform it into Ghana—a name he deliberately chose to evoke the ancient West African empire—and to forge a unified, industrialized, and socialist Africa that would transcend the fragmentations of colonial rule. For Nkrumah, political independence represented merely the opening gambit in a larger revolutionary project that sought to harmonize Africa's communitarian heritage with a rationally planned socialist future.

In Consciencism (1964), he articulated this vision with characteristic philosophical precision: "Any meaningful humanism must begin from egalitarianism... must lead to objectively chosen policies for safeguarding and sustaining egalitarianism. Hence, scientific socialism." The liberation of the individual, he argued, could emerge only through the conscious reconstruction of society along rational, collective lines—a project that would require both theoretical sophistication and unwavering political commitment.

Ghana Under Nkrumah: Utopian Dreams and Authoritarian Drift

Post-independence Ghana became the laboratory for this audacious experiment—a nation compelled to invent itself from colonial fragments while forging unity across profound ethnic and regional divisions, attempting a precipitous leap into modernity. The optimism of independence (1957) soon yielded to the burdens of state-building. Ghana, like virtually all postcolonial African states, bore the cartographic scars of colonial borders that bore little relationship to cultural coherence or historical continuity (Davidson, The Black Man's Burden). Nkrumah’s answer was charismatic leadership: he styled himself “Osagyefo” (Redeemer), championed pan-African unity, and set in motion massive development projects like the Volta River Dam—a symbol of both progress and displacement. In his early years, there were gestures toward pluralism; but, as opposition mounted and economic crises loomed, Nkrumah tightened his grip. By 1964, Ghana was a de facto one-party state. The Preventive Detention Act became the instrument for silencing critics; unions and civil society were centralized; dissenters—including former allies—were detained without trial (Agyeman-Duah, 1987). The cult of personality rose as democratic accountability faded, establishing a pattern that would haunt postcolonial Africa for decades.

Nkrumah's embrace of "scientific socialism" was neither idiosyncratic nor isolated. Across postcolonial Africa, the independence generation embarked upon an urgent search for development models that promised both rapid modernization and social justice: Nyerere's Ujamaa in Tanzania, Senghor's Negritude-inflected socialism in Senegal, and Cabral's liberation praxis in Guinea-Bissau.The theory was that traditional African societies were fundamentally egalitarian and could be reawakened through rational, planned development guided by scientific principles (Nkrumah, Consciencism; Wiredu, 1996).

Fanon warned that postcolonial states risked recreating the hierarchies of colonialism under new banners; Mbembe, in On the Postcolony, dissected how liberation rhetoric could so easily transmute into new forms of domination. Wiredu, echoing Popper’s warning against “closed societies,” cautioned that any “science” of society that foreclosed contestation was dogma by another name. “The party-state that proclaims to know ‘the people’s will’ quickly becomes indistinguishable from the colonial bureaucracy it overthrew” (Fanon).

Critics, both African and Western, were quick to see the dangers. Fanon presciently warned that postcolonial states risked reproducing colonial hierarchies under revolutionary banners; Mbembe, in On the Postcolony, dissected the mechanisms through which liberation rhetoric could transmute seamlessly into novel forms of domination. Wiredu, echoing Popperian critiques of "closed societies," cautioned that any purported "science" of society that foreclosed contestation was merely dogma by another name. As Fanon observed with bitter clarity: "The party-state that proclaims to know 'the people's will' quickly becomes indistinguishable from the colonial bureaucracy it ostensibly overthrew."

In Ghana, scientific socialist theory assumed concrete form through projects like the Volta River Dam, which required not only Western capital and technical expertise but also the displacement of thousands of rural inhabitants and the systematic suppression of local resistance (Meredith, The State of Africa). Nkrumah's growing intolerance for economic counsel from figures like W. Arthur Lewis and his increasing resort to preventive detention exemplified the characteristic trajectory of high-modernist projects: the conviction that revolutionary ends—national unity, rapid modernization, socialist transformation—could justify virtually any means.

The Postcolonial Double Bind: Structural Dilemmas and Institutional Fragility

The path Nkrumah charted cannot be understood merely as the product of personal ambition or ideological excess. The "double bind" of postcolonial leadership (Bayart, The State in Africa; Mamdani, Citizen and Subject) was structurally acute: inherited states lacked both administrative depth and civic coherence while facing overwhelming expectations for rapid development and national integration, in societies riven by deep ethnic and regional loyalties, shallow bureaucratic institutions, and the persistent threat of external intervention.

To unify, they centralized; but in centralizing, they often undermined the pluralism and participation that democracy required. Charisma, so essential to legitimacy (Weber), risked degenerating into personality cults and unchecked authority. The logic of "scientific" modernization—comprehensive economic planning, single-party rule, suppression of "backward" traditions—promised accelerated progress but sowed alienation and resistance. The “anti-politics machine” (Ferguson, 1990) was in full operation: politics became administration; social complexity was flattened in the name of science.

Comparative analysis confirms this pattern across postcolonial Africa. Nyerere's Ujamaa villages, initially voluntary experiments in collective agriculture, became increasingly coercive; Kenyatta's market-oriented Kenya, while less centralized, entrenched ethnic patronage and deep inequality (Berman & Lonsdale, 1992). The tragedy, as Fanon and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o insisted, was that liberation movements risked becoming the very instruments of domination they had fought to overthrow

Ghana's Democratic Renaissance: Institutional Pluralism and the Limits of Certainty

Nkrumah's regime fell in 1966 through Operation Cold Chop, a military coup that embodied both internal contradictions and the ironic consequences of educational expansion. Luttwak observed with characteristic wit that Nkrumah "was defeated by his own success": by educating the masses and expanding the elite, he fostered precisely the critical consciousness that ultimately undermined his authority. The decades that followed were turbulent: coups, military rule, and stalled development.

Yet, in the 1990s, Ghana pivoted—restoring multi-party democracy, strengthening civil society, and instituting reforms that insulated key institutions (Gyimah-Boadi, 2008; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Material resources—gold, cocoa, oil—remained crucial, but Ghana’s relative stability and growth have been attributed as much to institutional pluralism and checks-and-balances as to wealth (North, Wallis & Weingast, 2009). Unlike the paradigmatic “resource curse,” Ghana’s trajectory demonstrates that institutional design can mediate the path from extraction to shared prosperity.

Lessons for Transformational Leadership

What insights then does Ghana's complex trajectory offer for understanding transformational leadership more broadly? The African experience provides a crucial laboratory for examining universal questions about transformation, power, and democratic governance:

Institutional Pluralism and Adaptive Capacity: Effective reform requires both normative vision and robust institutional mechanisms for dissent, error correction, and democratic contestation. Transformation without accountability becomes domination.

Epistemic Humility and Local Knowledge: As Nyerere later acknowledged, imported models—regardless of their scientific pretensions—must adapt to local realities or risk disaster (Scott, Seeing Like a State). Universal principles require contextual translation.

The Limits of Technocratic Control: Popper’s “piecemeal engineering” and Ngũgĩ’s warnings against elite betrayal both speak to the need for humility, responsiveness, and ethical guardrails.

Democracy as Endogenous Resource: Gyekye and Mbembe emphasize that democratic practices and public reasoning are not foreign add-ons but vital expressions of human dignity and agency. Pluralism is the antidote to domination, whether colonial or postcolonial.

The Corruption of Absolute Ends: The monopolization of truth corrodes trust, incites resistance, and leads reformers to mimic the violence they once opposed (Fanon, Mbembe). (Fanon, Mbembe). Revolutionary virtue without institutional constraints becomes revolutionary terror.

Conclusion: An Unfinished Humanist Project

Nkrumah's humanist-socialist vision remains unfinished business. Ghana's historical trajectory—simultaneously hopeful, tragic, and redemptive—demonstrates that there isno "scientific" shortcut to social justice. The dream of transformation endures only when anchored in epistemic humility, ethical pluralism, and institutional adaptability. The enduring challenge for Africa and the world is to sustain the emancipatory promise while keeping it open, contested, and unfinished—not planned from above by technocratic elites, but earned through dialogue, dissent, and ongoing struggle.

References:

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Crown Business.

Agyeman-Duah, B. (1987). Nkrumah's Ghana and East Africa: Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda, 1958-1972. Associated University Presses.

Bayart, J.-F. (1993). The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly. Longman.

Berman, B., & Lonsdale, J. (1992). Unhappy Valley: Conflict in Kenya and Africa. James Currey.

Davidson, B. (1992). The Black Man's Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State. Times Books.

Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press.

Ferguson, J. (1990). The Anti-Politics Machine: Development, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. University of Minnesota Press.

Gyekye, K. (1996). African Cultural Values: An Introduction. Sankofa Publishing.

Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2008). Ghana's Fourth Republic: Championing the African Democratic Renaissance. Ghana Center for Democratic Development.

Luttwak, E. (1968). Coup d'État: A Practical Handbook. Harvard University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press.

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the Postcolony. University of California Press.

Meredith, M. (2005). The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence. Free Press.

Nkrumah, K. (1964). Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-colonization. Monthly Review Press.

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., & Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge University Press.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press.

Wiredu, K. (1996). Cultural Universals and Particulars: An African Perspective. Indiana University Press.