I am disgusted. Venezuela's collapse is a moral catastrophe. Yet Trump's reckless raid forces a perverse defense—America's strongman-in-chief just proved that toppling a dictator through illegal violence can be worse than the dictator himself.

On January 2 US Special Forces violated Venezuelan sovereignty, seized Nicolás Maduro, and paraded a sitting head of state into American custody. "Law enforcement" was staged as prime time spectacle—an act of executive vandalism that shatters the fragile remains of our global legal order.

Make no mistake: Maduro built a predatory regime. UN investigators documented systematic torture, forced disappearances, and more than 18,000 extrajudicial killings. He eviscerated constitutional democracy through court-packing, a parallel constituent assembly, and rigged elections—perfecting abusive constitutionalism. His so-called economic policy was organized looting: a 75% GDP contraction, hyperinflation deployed as social control, over $300 billion siphoned off by boligarchs while driving 7.7 million people into exile. None of this is defensible.

Yet, Trump’s operation is worse in kind. It bypassed all legitimate accountability mechanisms—ICC, OAS, UN—exposing how a “rules-based order” operates at the discretion of power. It annihilates international law, flagrantly violating UN Charter Article 2(4) by using unilateral force without armed attack or Security Council authorization—narco-trafficking does not justify self-defense under Nicaragua-case jurisprudence. The raid may well meet the Rome Statute threshold for aggression—Nuremberg’s “supreme international crime”—and trashes jus cogens norms of sovereignty and territorial integrity. Under Just War Theory, the action fails every test: no legitimate authority, no last resort, no proportionality, no right intention. Abducting a sitting president for domestic prosecution obliterates head-of-state immunity and weaponizes criminal law as regime-change.

The humanitarian crisis is real; but turning Venezuelans into props for American domestic appeasement or commercial interests is both illegal and immoral.

This is not a choice between Trump and Maduro; it's a choice between law and lawlessness. Once our legal order disappears, what restrains Russia in Kyiv or China in Taipei?

Congress must reassert its war powers. The UN General Assembly must convene an emergency session to demand accountability. Democratic nations must condemn the US. The ICC should investigate.

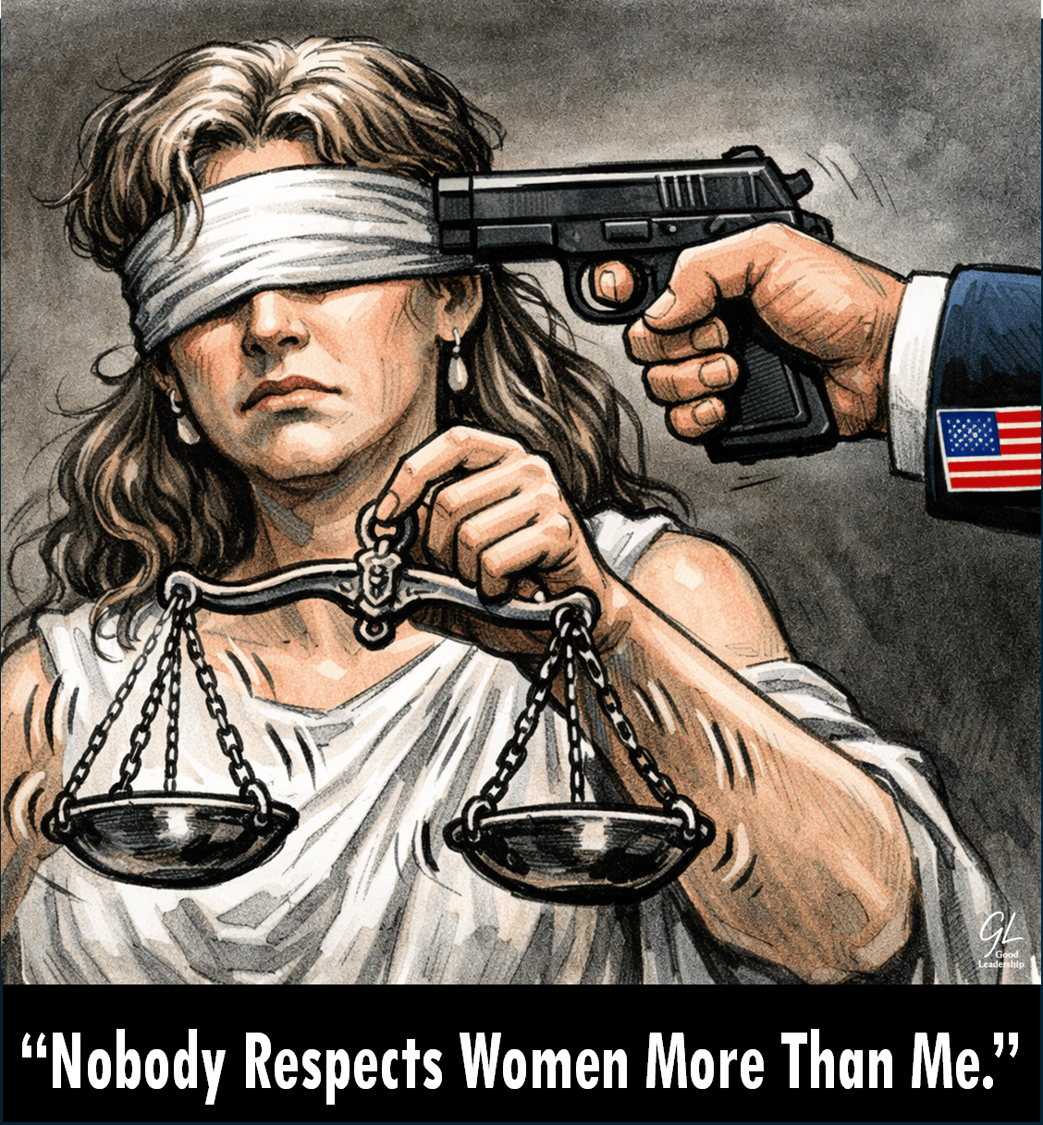

Perhaps most damning is the underlying psychology: Trumpism isn’t about justice; it is narcissistic domination as spectacle, contempt for all constraint, and crudest friend-enemy Manichaeism. Law enforcement becomes theater; foreign policy collapses into personal vendetta. As Hannah Arendt warned, when pathology becomes policy, governance degrades into strongman fantasy.

Trump supporters may cheer their triumph, but democracies only survive by constraining narcissistic autocrats—especially their own.

#Leadership #InternationalLaw #RuleOfLaw #WarPowers #Accountability #OurYearOfCourage

Source: Internet

Selected Q&A

Q- The argument that the United States acted unlawfully collapses under basic legal scrutiny and ignores decades of state practice. International law is not suicide law. UN Charter Article 2(4) is not absolute and has always been interpreted alongside Article 51 self defense when a regime actively enables transnational narcotics trafficking terrorism and threats to regional security. Venezuela under Maduro has been formally designated by US courts and agencies as a state sponsor and facilitator of narco terrorism with indictments issued by an Article III court. Jurisdiction flows from the crime not the comfort of the perpetrator. There is no rule in international law granting criminal immunity to de facto rulers engaged in transnational crime. States have repeatedly exercised extraterritorial law enforcement and military power when host states are unwilling or unable to address threats. This is established state practice not lawlessness. Appeals to the ICC or UN Security Council are unserious when veto politics shield criminal regimes. Enforcement of law against narco states strengthens international order. Allowing criminal sovereignty destroys it.

A- The comment collapses domestic criminal jurisdiction, self-defense under the UN Charter, and extraterritorial law enforcement into a single permissive doctrine of force. That is legally untenable. First, Article 2(4) does not “collapse” under Article 51. The ICJ has been explicit—from Nicaragua v. United States (1986) through Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (2005)—that self-defense requires an “armed attack” attributable to a state, not merely grave transnational criminality tolerated or enabled by it. The Court has repeatedly rejected the “accumulation of events” theory when it dilutes the armed-attack threshold into generalized insecurity. Second, U.S. domestic indictments do not generate international jurisdiction to use force. International law distinguishes sharply between prescriptive jurisdiction (the right to legislate and indict) and enforcement jurisdiction (the right to act coercively on another state’s territory). The latter is categorically prohibited without consent or Security Council authorization. Third, the claim that there is “no rule granting criminal immunity to de facto rulers” is a category error.

Head-of-state immunity is not criminal immunity in substance; it is procedural immunity ratione personae, affirmed by the ICJ in Arrest Warrant (DRC v. Belgium). It bars foreign domestic enforcement while in office, regardless of the alleged crimes, precisely to prevent unilateral coercion by powerful states. Fourth, the “unwilling or unable” doctrine remains contested and does not authorize regime-change capture operations. Even its most expansive formulations (advanced by the US and a small group of allies) concern non-state armed actors, not the forcible seizure of a sitting head of state for domestic prosecution. No opinio juris supports extending that doctrine to full-scale violations of territorial sovereignty against another government. Treating this as “established state practice” is nonsense—a methodological error international lawyers have warned against for decades. Finally, the claim that bypassing the ICC and Security Council “strengthens international order” reverses the logic of the Charter system. International law is indeed not “suicide law.” But neither is it prosecutorial vigilantism. Criminal sovereignty is not what destroys international order; criminalizing sovereignty through unilateral force does.

Q- You are not making any sophisticated distinctions here. You are simply restating settled doctrine and pretending that it resolves a problem that it does not. The baseline of Article 2(4), the exception of Article 51, and the reluctance of the ICJ to accept in the abstract an accumulation theory are all understood. Freezing the law sited at its most convenient point does not address the modern question of attribution, imminence, and state unwillingness, simply repeating the Nicaragua and Armed Activities cases like a spell. You also seem to prefer to compartmentalize jurisdictional distinctions in a way that state practice has shown lacks validity for decades. While prescriptive jurisdiction, enforcement jurisdiction, and self-defense are distinguished, your argument presumes that these never interact, which is simply and plainly wrong and avoids the issue at hand. International law is not satisfied by having a neat arrangement of jurisdictions. It is tested by the reality of the situation, a series of actions, and the resultant consequences. Simply stating that opposing views are legally untenable does not make it true.

A- Your comment sharpens the debate, but it still conflates legal development with normative displacement and treats contestation as if it were settlement. First, on “freezing the law at its most convenient point”: citing Nicaragua and Armed Activities is not incantatory formalism; it is fidelity to the only authoritative interpreter of the Charter system we have. The ICJ’s reluctance to endorse accumulation, broaden attribution, or dilute the armed-attack threshold is not doctrinal inertia but a constitutional choice within international law. In legal-theoretical terms, the Court has repeatedly opted for rule-preserving restraint over adaptive elasticity precisely because the prohibition on force is a secondary rule of recognition for the system as a whole. To argue that the law must “move on” because factual patterns have changed is not jurisprudence; it is teleological revisionism without an accepted law-making mechanism. Second, on attribution, imminence, and unwillingness: these are indeed the hard problems—but they remain unsettled problems, not resolved doctrines.

The “unwilling or unable” test has never crystallized into customary international law: opinio juris is deeply divided, practice is concentrated among a small subset of powerful states, and crucially, no authoritative judicial body has endorsed it as a Charter-compatible basis for force against a state. From a Hartian perspective, this is not a penumbral case resolved by practice; it is a disputed candidate rule lacking acceptance by the relevant interpretive community. Contestation does not equal authorization.

Third, on the interaction of prescriptive jurisdiction, enforcement jurisdiction, and self-defense: of course they interact. But interaction is not fusion. The conceptual distinction is not scholastic tidiness; it is what prevents the collapse of law into power. The very point of separating prescriptive from enforcement jurisdiction is to deny that the existence of a crime (even a grave one) generates a unilateral right to coerce abroad. Once enforcement jurisdiction is allowed to piggyback on prescriptive reach plus threat perception, the prohibition on force becomes functionally optional. That is not “law tested by reality”; it is what Kelsen would have called a reversion to decentralised sanctioning, i.e. pre-legal international order. Fourth, your appeal to state practice over doctrine quietly assumes a positivism that international law itself rejects. Customary law requires not just repetition, but normative self-understanding. The fact that some states act as if they possess a right does not establish that right when other states persistently object and courts refuse to validate it. Otherwise, the strongest actors would become de facto legislators—a result the Charter system was explicitly designed to prevent. Finally, at the level of legal philosophy, the disagreement is not about sophistication but about what kind of legal order international law is meant to be. Your position treats international law instrumentally—as a toolkit to manage threats when institutions fail. Mine treats it constitutionally—as a framework that deliberately accepts enforcement inefficiency to prevent unilateral violence from being redescribed as legality.

You are right that international law is tested by reality. But it is tested as law, not as policy. The question is not whether new threats exist, but whether unilateral force is permitted to redefine the law meant to restrain it.

Q- It seems your position accepts prolonged impunity as the price of preserving procedural legitimacy. We clearly differ on that point. If international law has no answer when its mechanisms are structurally blocked, on what basis does it claim moral authority over outcomes?

A- No no no. ;-) I respect the passion, but this move fails. Justice is a higher-order good that must be preserved precisely when outcomes are intolerable. It is an illegitimate dichotomy to suggest that when law “doesn’t work,” we must break it. That frames a false choice: accept impunity to preserve legality, or abandon procedure to recover moral authority. This misunderstands both how international law claims authority and what its procedures are for.

First, it conflates blocked enforcement with normative failure. International law has always functioned under incomplete enforcement—because it governs sovereigns. Its authority does not lie in guaranteeing optimal outcomes in every case, but in stabilizing expectations, constraining escalation, and preserving reciprocity over time. Hobbes already understood this: unchecked unilateral force is not justice but the Leviathan in action. Second, it treats procedural legitimacy as merely instrumental and therefore dispensable. That is a category error in legal philosophy. Procedures are not ornamental. Law’s moral authority lies precisely in refusing to collapse into outcome-maximization by the powerful.

Third, the appeal to “structural blockage” smuggles in a self-authorizing exception. Who decides that mechanisms are blocked enough? Who judges imminence, necessity, or proportionality when acting outside them? In practice, the answer is always the acting state. That move replaces law with decisionism, not justice. Historically, this logic has been invoked far more often to justify domination than to prevent atrocity. Finally, the argument mistakes impatience with injustice for a theory of justice. Impunity is a moral failure—but so is the normalization of unilateral coercion. International law claims moral authority not by promising perfect accountability, but by keeping open the possibility of accountability without collapsing into force. The alternative is not moral clarity; it is a world in which every power declares its own exceptions—and calls them justice. Hence, the answer is to make the international system work, not to blatantly undermine it has Trump has been doing from the beginning (and as the US historically has often done).

Q- Would you think the same way if another criminal, Vladimir Putin, had been arrested in a similar operation?

A- That's a great question, but we need to make sure the test is legitimate in principle, ie iff the legal criteria remain constant. From the standpoint of international law - and justice, the answer does not turn on the moral quality of the target, but on the means, authority, and institutional pathway used. An extraterritorial military seizure of a sitting head of state without UN authorization, absent an armed attack, and outside an existing international judicial mandate would raise the same legal objections regardless of the individual. Law governs acts, not villains. The very reason we insist on procedures is that “exceptional criminals” are precisely when power most tempts itself into exception-making. Schmitt, not Kant, is the tradition that grounds legality in identifying the enemy. If powerful states can unilaterally abduct leaders they deem criminal, then jurisdiction collapses into capability. The result is not universal accountability but selective enforcement by force, which historically produces escalation, not justice. But careful: rejecting illegal means does not equal tolerating impunity. The alternative is not passivity but institutionalized accountability:

international arrest warrants, collective sanctions, diplomatic isolation, asset seizure, and—crucially—preserving the norm that force is constrained even against the worst offenders. That's precisely what Trump and other autocrats reject. But law’s authority lies in surviving precisely these hard cases.

In fact, Putin’s standing is categorically different from Maduro—Putin is under active ICC arrest warrant (war crimes; deportation of children) issued by a competent international court with jurisdiction accepted by Ukraine and supported by a broad coalition. This already places him inside an institutional accountability track. That said, international law distinguishes intervention from enforcement by force. Even where crimes are of the highest order (genocide, crimes against humanity, aggression), enforcement remains constrained. The UN Charter allows only: Security Council–authorized force, or self-defense against an armed attack (Article 51). Neither permits a coalition—or the US—to conduct a cross-border seizure of a sitting head of state for prosecution. That move would still violate Article 2(4), even for Putin. "Responsibility to Protect” allows collective action to stop ongoing mass atrocities, but not abduction.

In a nutshell, the worst criminals are often the "hardest" cases because they tempt shortcuts. If the international community were to abduct Putin by force tomorrow, it would not vindicate justice; it would ratify the principle that might makes jurisdiction. That principle would be seized immediately by every great power. Herein lies the challenge with narcissistic autocrats like Trump turning justice into personal war games.

Q- Nicolás Maduro is not a head of state, he is only a gangster. Edmundo González is the elected president, with 70% of the votes and recognised by most democracies in the world.

A- Ah very nice. Yes, that position draws indeed on real debates in international law, but overextends them in a way the law does not support. First, international law distinguishes legitimacy from legal status. Electoral fraud and lack of democratic legitimacy do not automatically erase a person’s status as de facto head of state. Customary international law has long separated recognition of governments from recognition of states, precisely to avoid making legal obligations hinge on political agreement. Maduro exercises effective control over territory, institutions, and armed forces; that is sufficient for functional head-of-state status for purposes of sovereignty, immunity, and the use-of-force regime, however illegitimate his rule may be. Second, non-recognition does not authorize unilateral force. Even where a regime is widely condemned or partially unrecognized, the prohibition on the use of force under Article 2(4) remains. Recognition doctrine affects diplomacy, sanctions, and treaty relations—not enforcement jurisdiction by military means. Otherwise, recognition would become a license to abduct rivals, a result international law has consistently rejected.

Third, the invocation of Edmundo González’s electoral mandate, while normatively powerful, does not alter the jus ad bellum analysis. International law does not permit external actors to use armed force to “install” a preferred government absent Security Council authorization or collective self-defense. The law deliberately resists converting democratic judgment into coercive entitlement, because doing so would internationalize civil conflicts and invite proxy wars. Fourth, the “gangster” framing collapses criminal responsibility into enemy status. That move is philosophically Schmittian: once someone is labeled criminal–enemy, law gives way to decision. Modern legal orders were built precisely to prevent that slide. Even pirates—hostis humani generis—are subject to legal process, not discretionary violence by great powers. Finally, the argument mistakes moral clarity for legal permission. One can coherently hold that Maduro is illegitimate, criminally liable, and unfit to govern—and still insist that accountability must occur through institutionalized mechanisms rather than unilateral force. That tension is not a flaw in the law; it is the price of avoiding a world where power decides legality.

Q- The USA is not a member of the ICC.

A- Exactly right. Non-membership has become a standing strategy for insulating American leaders from the very legal order the US demands others respect. It exposes the chronic asymmetry at the heart of the so-called rules-based order.

That said, calling for an ICC investigation is not incoherent simply because the US is not a party. ICC jurisdiction can still arise ratione loci where alleged crimes occur on the territory of a State Party (Venezuela is an ICC State Party), and—more importantly—through the normative and archival function of international criminal law. An investigation need not culminate in arrest to be legally meaningful: it establishes the juridical record, clarifies whether conduct meets the threshold of aggression or related crimes, and fixes responsibility in international law. U.S. non-membership blocks enforcement, not scrutiny. But again, that asymmetry is part of my critique: a state that claims to uphold a rules-based order while structurally exempting itself from its highest court reveals a profound legitimacy deficit.